Stephen Gill

A fascination with the mysteries and strangeness of the natural world threads Stephen Gill’s photography. This isn’t surprising; he has spoken of how his interest in the medium began with a concurrent fascination with what life looks like under a microscope. His 2012 series, Coexistence, made with water from a polluted pond in Luxembourg, echoes that personal history. While Gill looks intently, he also purposely obscures and complicates what we see. Relishing in chance and experimentation, his work has involved dipping negatives into the sea or directing sunlight onto a negative with the help of a magnifying glass; the resulting distortions offer up peculiar, idiosyncratic impressions of the world.

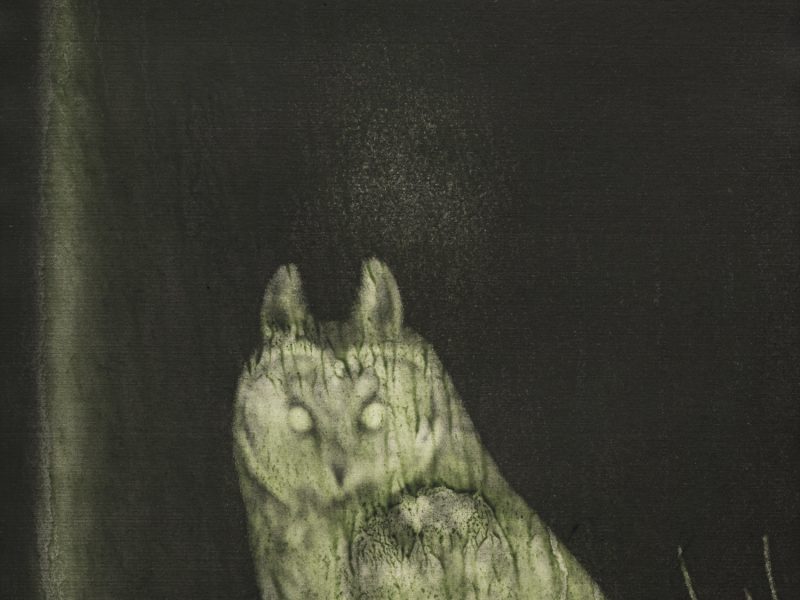

For his most recent series, Night Procession, Gill has moved from England, the setting for many of his series, and turned his eye on the landscape of rural southern Sweden and the nocturnal life teeming in this environment. “I started to imagine the creatures in absolute darkness on the forest floor driven by instincts and their will to survive,” he writes. “I thought of their eyes – near redundant in the thick of the night – and their sense of smell and hearing finely tuned and heightened.” Once again, he is searching the micro level for the unseen and the overlooked. It will be exciting to see how Gill uses the expertise of the Hariban studio to bring this project to new life.

– Michael Famighetti On behalf of the Jurors, Hariban Award 2017

Artist Statement

In March 2014, my family and I moved from east London to rural south Sweden where my partner Lena is from. I understood that these new surroundings would inform my work in very different ways and that nature would play a key role. I was looking forward to making work that did not feel restricted and suffocated by modern photographic technology nor would make an inaccurate projected impression of the natural landscape we had become part of.

On my many walks, I soon came to realise that this new, apparently bleak, flat and open landscape was in fact teeming with intense life. Small clues appeared during daylight hours that helped me understand the extent of activity during the night. Clusters of feathers, animal footprints of all sizes showing regular overlapping routes, gnawed branches, eggshells, ant hills, nibbled mushrooms and busy snails and slugs working through the feast provided from the previous night

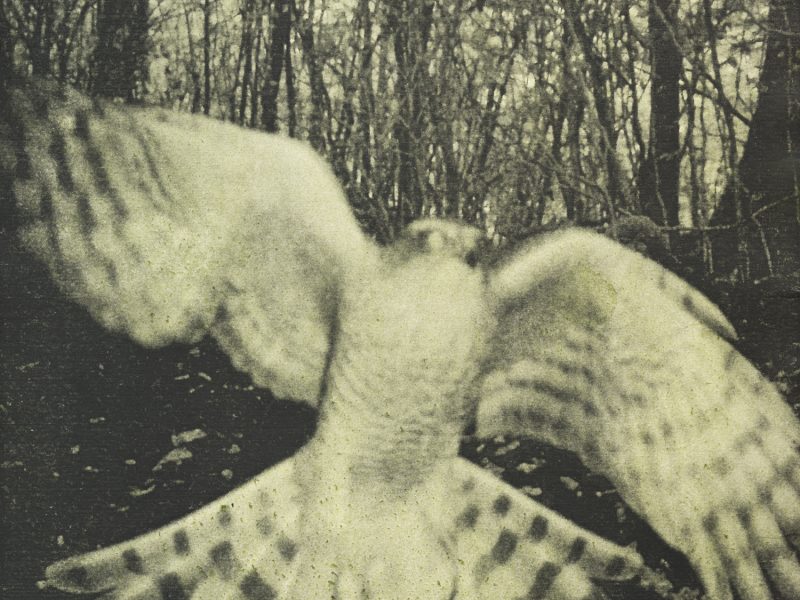

I started to imagine the creatures in absolute darkness on the forest floor driven by instincts and their will to survive. I imagined them encountering each other. I thought of their eyes – near redundant in the thick of the night – and their sense of smell and hearing finely tuned and heightened. Envisaging where this activity might unfold, coupled with a hopeful foresight, I placed cameras equipped with motion sensors, to trees, mostly at a low level, so that any movement triggered the camera shutter and an infra-red flash (which was outside the animals’ visual spectrum). The first results filled me with fascination and joy as they presented what felt like stepping off into another parallel and unearthly world. The silent photographs also seemed to invent sounds. This frame of mind and way of working took me back to my first ever photo project at the age of 13, sitting in the bathroom window of my parents’ house in Bristol with a 10-metre cable release, attached to the camera, attempting to photograph garden birds.

As time went on I started to think, if I were a deer where would I drink from, or if an owl where would I prefer to perch, and positioned cameras in such places. I was already composing the rectangular view in my mind’s eye – even though the nocturnal animals were absent – imagining they were there. Nature itself helped to decide the palette and the feel of the images as plant pigments were incorporated from the surrounding areas to make the final master prints.

I had grappled for many years with this idea of stepping back as the author of images to give space for chance and to encourage the subject to step forward. I had attempted this in various ways; for example, in 2005, by burying colour prints close to where they were made, as a collaboration, to entice the place itself to leave its physical mark on the images once they had been unearthed. Or, between 2009 – 2013, in the series Talking to Ants, I placed objects such as plant life, insects, seeds and dust from the place I was photographing inside the film chamber to create in-camera photograms creating a confusion of scale. Or, in 2012, in Best Before End, as a photographic response to the rise of high-energy drinks, I used the drinks themselves to part-process the film as they ate into the emulsion. These approaches added an element of uncertainty, without knowing exactly where the images would land, and relied on a point where intentions met chance with the hope that the subject itself could play a part, lead the way or become embedded in the finished images.

This time, though, it felt as if I was stepping out altogether, so that the subjects would orchestrate and perform and take on the role of author while at that moment I was likely to be sleeping. This was nature’s time to speak and let itself be felt and known.

Bio

Born in Bristol, U.K., Stephen Gill became interested in photography in his early childhood, thanks to his father and interest in insects and initial obsession with collecting bits of pond life to inspect under his microscope. Stephen’s photographs are held in various private and public collections and have also been exhibited at many international galleries and museums including London’s National Portrait Gallery, The Victoria and Albert Museum, The Museum of London, Agnes B, Victoria Miro Gallery, Christophe Guye Gallery, Sprengel Museum, Tate, Centre National de l’audiovisual, La Filature, Archive of Modern Conflict, Gun Gallery, The Photographers’ Gallery, Palais des Beaux Arts, Leighton House Museum, Haus Der Kunst and has had solo shows in festivals including – Recontres d’Arles, The Toronto photography festival, Images festival – Vevey and PHotoEspaña.

■最優秀賞-スティーブン・ギル

Night Procession

スティーブン・ギルの作品は、神秘と不思議に満ちた自然界への好奇心によって編み出されている。 彼は顕微鏡をとおして見た生き物への興味が、そもそも写真を撮り始めるきっかけになったと語って いるが、それは特に驚くことではない。たとえば 2012 年にギルが発表した『Coexistence(共存)』 というシリーズは、ルクセンブルグの汚染された池の水が使われていた。ギルはじっくりと物事を観察 もするが、いっぽうで被写体となるものを意図的に遮ったり複雑にしたりもする。さらに偶然性や実 験性も好み、海水にネガフィルムを浸したり、虫眼鏡で太陽の光を集めて完成させた作品は、歪曲 されていて奇妙で独特の印象を与える。最新作となる『Night Procession(夜の行進)』は、それ までほとんどの作品の舞台となっていた母国イギリスを離れて制作された。南スウェーデンの郊外に ある自然に目を向け、その地で繰り広げられる闇の世界がテーマである。彼は「森にいる動物たち は、完全な暗闇の中で生き抜くための本能に頼って暮らしていると思えてきた」と綴っている。また「森 で暮らす彼らの目は暗闇ではほとんど役に立たないが、(逆に)嗅覚と聴覚をひときわ研ぎ澄まして いるのだろう」とも。つまり、今回のシリーズをとおしてギルは、我々が見えなかったものや普段見過 ごしていたものなどを、ごく小さな限られた世界から探し出してきたといえるだろう。便利堂の高度な プリント技術によって、今回のギルの受賞作がどのように生まれ変わるのかとても楽しみにしている。

– マイケル・ファミゲッティ Hariban Award 2017 審査員代表

Night Procession

2014年3月、わたしは家族とともに、西ロンドンからパートナーのレナが生まれ育った南ス ウェーデンに引っ越しました。この新しい環境がわたしの制作にかなり影響を与え、しかも、自 然がとても重要な役割を果たすことになるだろうということに気づきました。わたしは現代の写 真の技術に制限されたり、息詰まりを感じたりしない作品を生み出すことを楽しみながら、自 分もその一部である自然の景色について、まちがった印象を与えないものようなものを作りた いと考えました。

わたしはよく散歩に出かけたのですが、すぐにこの新しく荒涼と平坦に拓けた景観が、実は様々 な生き物に溢れていることに気がついたのです。また、昼の間に少しばかりの手がかりを見つけ ると、夜の動物の活動をより理解することもできました。例えば、一箇所に集まった羽毛や道に 重なり合うように残された色々なサイズの動物の足跡、噛み切られた枝、卵の殻、アリの巣、 少しかじられたキノコ、動き回るカタツムリ、前夜の餌食になった肉に張り付くナメクジなどです。

サバイバルしなければならないという本能によって、森の漆黒の中を動き回る動物のことを想 像し、彼らがお互いに遭遇する様子はどんなだっただろうかと考えました。また、夜が更け彼ら の視覚が必要でなくなるや、今度は嗅覚と聴覚を整え、研ぎ澄ますのだろうと想像したりもしました。

そんな彼らの行動がどういった場所で展開されるかを自分なりに想定し、モーションセンサーを 搭載したカメラを木々の低い場所に設置し、もしなんらかの動きがあればカメラのシャッターと 赤外線フラッシュ(動物には見えない可視スペクトル)が同時に作動するようにしたのです。

そして、初めて得られた結果はわたしを魅了しました。なぜなら現世界とパラレルに起こっている 別世界に踏み入れたような感覚を覚えたからです。それら静寂の写真はまるで音を創り出して いるようにも思えました。ブリストルにある実家の浴室の窓辺に座り、カメラに取り付けた10 メートルほどのコードを使って、庭に来る鳥を撮影していた13歳の自分のようで、初めて写真 に取り組んでいた頃のことを思い出させてくれたのです。

もし鹿だったらどこで水を飲むだろうか、フクロウであれば木のどの辺りの枝に停まるだろう か…、時間を経るごとに考え、そういった場所にカメラを設置したりもしました。そこに夜行性 の動物がいなくても、まるで彼らがそこにいるものと想定して心の目で長方形の写真の風景を 作りあげるようになりました。最終的なプリントを作るときには撮影した森から採取した植物の 樹液を用い、写真の色とイメージそのものを決定するのに役立てました。

わたしはこれまでアーティストとしての主張を控えめに、被写体そのもので作品を作り、偶然性 を作品に取り込むという風に、色々な方法を長年にわたり試みてきました。例えば2005年に カラープリントを撮った場所の近くにその写真を埋め、しばらくしてそれを掘り起こすことで、 そこに埋もれた場所の痕跡を自然とのコラボレーションとして写真に残すという試みをしま した。2009年から2013年に制作した「Talking to Ants(蟻たちとの対話)」というシリーズ では、カメラの内部に撮影していた場所から採取した植物や昆虫、種子、埃などを入れて、そ れらと一緒に風景写真を撮ることで、植物や昆虫のサイズを混同させるように見せました。ま た、2012年の「Best Before End(最後の前の最高)」では、高エネルギー飲料の人気に対 する写真的な取り組みとして、その飲み物を混ぜた液でフィルムを現像しました。こういった 制作過程では、どういった画像が現れるのかまったく予測できないばかりか、不確実の要素は、 時に被写体の役割を果たしたり、導いてくれたり、そのまま画像の一部として組み込まれること もありました。

今回のシリーズ「Night Procession(夜の行進)」ではあえてその現場から離れ、まさにその撮 られた瞬間わたしは眠っているのですが、その間も森の被写体たちはオーケストラのための作 曲をしたり、演者のような役割を担っていたというわけです。今回のシリーズをとおして、自然そ のものが自ら語ってくれることを、我々の方が認知し感じとる必要があるのではないだろうかと 問いかけています。

– スティーブン・ギル

Stephen Gill スティーブン・ギル

1971 年、イギリス・ブリストル生まれ。幼少時に父親の影響で写真をはじめ、10 代は地元の写真ス タジオで家族写真の撮影や古い写真の修復を手伝う。スピード現像ラボに勤務した後、フィルトンカレッジの基礎コースで写真とアートを学ぶ。ロンドンのマグナムフォトでアシスタントを務め、写真家とし て独立。以来、日常をユニークな視点で切りとった新しい表現を切り拓いてきた。代表作に、写真の 上から実際の花や植物を載せて撮影した「Hackney Flowers」、世界各国のトイレに設置されたトイレッ トペーパーの端を折ったものを収集して撮った「Anonymous Origami」、目立つように蛍光色の服を着 ている鉄道や町の工事現場の作業員が、むしろ景色の中に馴染んでしまっているという矛盾に着目し た「Invisible」などがある。長く住んだイーストロンドンを離れ、現在はスウェーデンを拠点に活動中。

Grand Prize WInner

Series Title

Night Procession

Website

Category

Hariban Award 2017